|

Women

saved Shaker Lakes from freeways

Monday, September 25, 2006

Michael O'Malley Plain Dealer Reporter

Catherine

Fuller, who turns 88 next month, still shudders at the idea of a

superhighway cutting through the heart of the Shaker Lakes nature

preserve, destroying 200 acres of wildlife and wiping out hundreds

of nearby homes.

She first got wind of the plan 43 years ago at a garden club meeting

at the North Park Boulevard home of Mary Elizabeth Croxton, just

across the street from the lower Shaker Lake.

"We were horrified," she said. "We immediately said, It's got to be

stopped, no question about it.' "

|

|

|

Catherine Fuller, 87, and

Kathleen Barber, 82, stand on a deck in the middle of the Shaker

Lakes nature preserve. The two women were on the front lines 40

years ago in a battle to stop two freeways from running through

Shaker Lakes.

photo Joshua Gunter Plain Dealer |

|

|

The

meeting of 11 women was a call to war, pitting ladies' garden clubs

against a powerful, steam-rolling freeway industry and a forceful

county engineer while sowing the seeds of a momentous grass-roots

uprising that drew national media attention.

"It wasn't

hard to mobilize, said Kathleen L. Barber, 82, one of the many

frontline activists in the fight. "People were outraged. When your

home is threatened and your community is threatened, you mobilize."

Fuller and

Barber are founding members of the Shaker Lakes Nature Center, which

celebrates its 40th birthday this month. The center was born in the

heat of the freeway fight and stands today as a monument to victory.

"The whole

East Side should take those ladies out for a couple of cold beers,"

said Tom Bier, an urban studies professor at Cleveland State

University. "Their battle marks one of the most significant bits of

history in the last 50 years because of what didn't happen. They

actually stopped the highway industry, and that's big."

A half

century ago, when America was linking its cities with high-speed

highways, no community was safe from the threat of earthmovers and

concrete trucks, not even the richest community in the nation --

Shaker Heights. The 1960 census showed that Shaker Heights had the

highest median household income in the land, but that had no effect

on the freeway planners.

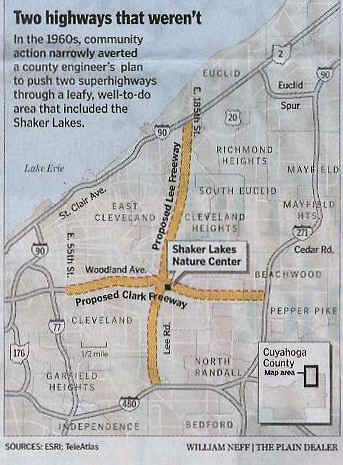

In October

1963, Cuyahoga County Engineer Albert Porter unveiled the proposed

Clark Freeway, an east-west route linking Cleveland with Pepper

Pike.

It was to run east from East 55th Street near Broadway in Cleveland

to Interstate 271 in Pepper Pike. It would have ripped through the

Shaker Lakes and cut a swath along Shaker Boulevard into Beachwood.

Once the Clark was finished, the plan was to run a north-south

route, called the Lee Freeway, connecting I-90 near Lake Erie to the

Ohio Turnpike. The Clark and the Lee were to intersect where the

Shaker Nature Center is today. |

|

|

|

"To exchange this park of irreplaceable beauty for a mass of

concrete roadway would be an unthinkable act of vandalism," Croxton

of the Village Garden Club told the New York Times in October 1966.

The two freeways would have taken 1,370 homes and 105 commercial

properties in Cleveland, Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights,

including the homes of such prominent people as Cleveland Orchestra

conductor George Szell, U.S. Ambassador to Austria Milton Wolf and

Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes.

They would have also destroyed the final resting place of early

Shaker settler Jacob Russell, a Revolutionary War soldier buried

near Horseshoe Lake.

Croxton and dozens of other garden club ladies, joined by a broad

coalition of residents and environmentalists, launched a massive

campaign led by public officials and prominent residents.

But Porter pushed hard, saying a delay in the project would result

in losing millions of federal highway dollars. He called Shaker

Lakes a "dinky little park and two-bit duck pond" and described the

opposition as a "chintzy, spoiled bunch."

Porter, who was also the county's Democratic Party chairman, was

driving a steamroller that not even Republican Gov. James Rhodes

could stop.

In March 1966, George Condon, a columnist for The Plain Dealer,

wrote, "No doubt the Clark Freeway will go precisely where County

Engineer Porter [says] it will go and the public be damned. But

wouldn't it be nice if ... human values and natural resources took

precedence over the arbitrary plans of the engineers?"

Yes, answered the "chintzy, spoiled bunch," refusing to roll over.

"Better ducks than trucks!" they cried, mounting more public

pressure against Porter and his highway men.

After a seven-year battle, Porter realized he was outgunned. In

1970, buckling to the growing protest, Rhodes quietly took the

freeways off the map.

"We had a wonderful party," Barber said. "I remember a great public

sigh of relief."

Killing the Clark and the Lee also killed tentacles that would have

reached through Highland Heights, Richmond Heights, Gates Mills and

other Cuyahoga County suburbs.

Six years after the battle, The Plain Dealer reported that Porter

had created an employee payroll kickback scheme that raised millions

of dollars for himself.

In November 1976, he was voted out of office. That same year, the

nature center opened a small retail shop called the Duck Pond Gift

Store.

In 1977, Porter was convicted of theft in office. He died in 1979.

© 2006 The Plain Dealer |

|