Can Shaker Square’s rescuers come up with

compelling new vision for a struggling Cleveland landmark?

Steven Litt May 12,

2023 |

|

|

|

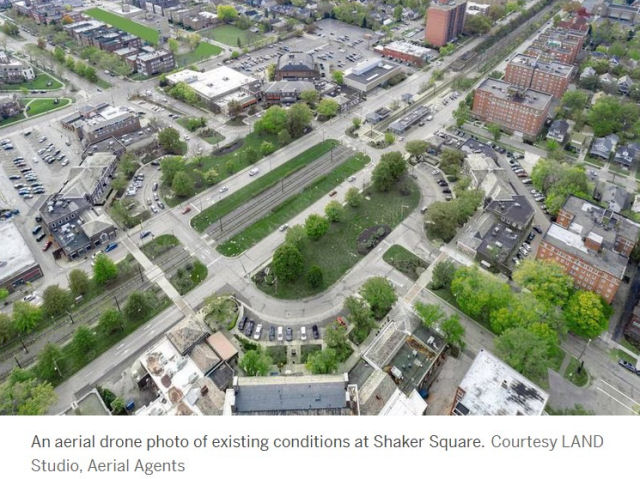

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Shaker Square was the

latest word in upscale urban innovation when it opened in

1929 as one of America’s first automobile- and

transit-oriented shopping centers.

Built by the

Van Sweringen brothers, the tycoons who went bust in the

Depression, the square featured Georgian Revival-style

buildings wrapped in an octagon around a five-acre central

landscape. The “square” is bisected by a rapid transit line

connecting the suburb of Shaker Heights to the east, and

Terminal Tower downtown, to the west, both of which the

brothers also built.

Yet after serving for decades as a beloved regional

destination for shopping and dining, Shaker Square occupies

an uneasy boundary line of race and class between redlined

neighborhoods on Cleveland’s East Side and affluent suburbs

further east.

It also faces challenges from decades

of disinvestment and competition from newer East Side

suburban shopping centers including the Van Aken District in

Shaker Heights, Legacy Village in Lyndhurst and Pinecrest in

Orange.

Key storefronts are vacant. Leaky roofs cry out for repairs,

and white-painted columns, arches, and pediments are rotting

and peeling. Awnings are faded and drooping. Sunken areas of

pavement collect big puddles after heavy rains.

But the first signs of a turnaround are

also visible this spring. Trees at the square have been

pruned. Planting beds have been tidied. Security cameras and

lighting are getting fixed.

The changes are early indicators that

the square, a Cleveland neighborhood treasure, is under new

ownership dedicated to ensuring its long-term survival.

Using a $12 million loan from the City

of Cleveland, two nonprofits, Cleveland Neighborhood

Progress (CNP), and Burten, Bell, Carr, Development Inc.

(BBC), bought the square from creditors last August.

Their goals are to stabilize the

property, prepare it for sale to new for-profit ownership

within five years, and then reimburse the city for at least

half of the $12 million, or more, depending on the sale

price. The remainder would be considered a forgivable loan

from the city, said Tania Menesse, CNP’s president and CEO

since 2020.

Since taking ownership, CNP and BBC

have raised more than $5 million to tackle a list of repairs

with an estimated total cost of nearly $8 million according

to a recent assessment.

While fundraising continues, repairs on

roofs, plumbing, and wiring are about to get underway this

summer. Special events, in addition to the popular weekly

North Union Farmers Market, held on Saturdays from April to

early December, are being planned to make the square feel

active and lively.

Launching a new plan for the future

Merchants say they’re generally pleased

by the work so far, and by the transparency and

responsiveness of their new, nonprofit landlords. But they

want to know, long term, where the square is headed.

So do BBC and CNP. That’s why they’re starting a new

long-term plan for the property. The goal is to unite Shaker

Square’s community — including merchants, business owners

and area residents — around a vision to help guide the

search for a new long-term, for-profit owner.

By the end of May, the nonprofits told

cleveland.com and The Plain Dealer, they’ll release a

request for proposals from planning consultants. Information

about the project and a contact link for suggestions will be

posted on the square’s new website,

shakersquare.com, which went live quietly during the

last weekend in April.

So here’s the big question: Can the

nonprofits succeed? Or to put it more accurately, can they

get it right this time?

That’s a complicated question because

the new plan will follow

a previous effort, led by a steering committee headed by

CNP, which sparked anger and recriminations in 2019.

In November that year, a couple of weeks before

Thanksgiving, a crowd

gathered at the square with a bullhorn and signs to

protest the core recommendation of the earlier plan: closing

Shaker Boulevard’s east- and westbound lanes, which bisect

the square, and routing through traffic around its

perimeter.

Planners from the landscape architecture firm of Hargreaves

Associates, now Hargreaves Jones, had argued that closing

the lanes was the best way to improve the square’s public

spaces and help make it profitable.

But business owners said the proposal

would cause gridlock and confusion, and make it harder for

customers to reach their front doors.

CNP shelved the $400,000 planning

effort. Then COVID hit, and the square entered a period of

instability that led to the threat of foreclosure and a

sheriff’s sale.

Anchor tenants including the

restaurants Fire, Yours Truly, and Balaton shut down. Some

tenants stopped paying rent, and the square’s condition

degenerated during 18 months of receivership, Menesse said. |

Why the

new push might succeed

There are solid reasons to believe the

nonprofits might have better luck with their new planning

effort than with the last one.

First, the businesses on the square, including Dave’s

supermarket, the Atlas movie theater, and the Sasa, EDWINS,

Zanzibar, and Vegan Club restaurants remain deeply

committed.

Merchants see the square’s location

between the city and affluent suburbs further east as a

virtue. For them, it’s a place to heal racial divisions, to

build local wealth, and to capitalize on its proximity to

University Circle and the nearby Cleveland Clinic.

“I describe it as a melting pot,’’ said

Renay Fowler, who co-owns Fashions by Fowler and describes

her typical customers as mature women who are “going

somewhere special where they want to look great.” She sees

the square’s diverse clientele as unique in Northeast Ohio.

So does Elina Kreymerman, owner of Shaker Square Dry

Cleaning and Tailoring. “We love it here,’’ she said. “Our

business is very diverse, and it’s good. We accommodate

everybody.”

The nonprofits that now own the square

are fully empowered to think long-term about its future.

That wasn’t the case five years ago when an affiliate of

Coral Co., the Cleveland firm that had owned the square

since 2004, was struggling under an $11 million mortgage. In

late 2020, Wilmington Trust and CWCapital Asset Management

filed to seize the square through foreclosure.

When the nonprofits purchased the square in 2022, they

averted the possibility of seeing the square sold to an

out-of-town buyer without a long-term interest. CNP now has

a 90% stake in SHSQ LLC, held through New Village Corp., a

CNP subsidiary. BBC holds 10% of the equity in the LLC.

“We can raise capital and we can make

good decisions for the community in a way that a for-profit

can’t,’’ Menesse said. The repairs now led by the nonprofits

are intended to last 20 to 30 years, giving the square a new

measure of stability. Changing

politics

Then too, the political and community

development structure around the square has changed. Ken

Johnson, the former councilman who represented Ward 4, which

includes the square, was sentenced in 2021 to serve six

years in prison and pay $740,000 in restitution for stealing

community development funds from the city and federal

government. Ward 4 is now represented by Councilwoman

Deborah Gray.

Also, five years ago, the area didn’t have a viable

community development corporation like those that have

supported revitalization efforts in other neighborhoods

across the city.

Since then, BBC expanded its service

area east from the Kinsman neighborhood into Buckeye, which

includes the thriving Larchmere Boulevard commercial and

residential corridor north of Shaker Square, and the

struggling Buckeye Road commercial corridor, south of the

square.

The earlier plan in 2018-2019 was based

on what now appears to have been a mistaken premise that

improving Shaker Square’s public spaces would be enough to

drive the property to financial profitability.

“There were some really fantastic ideas

that came out of that plan,’’ said Joy Johnson, BBC’s

executive director. But because of doubts about the wisdom

of closing Shaker Boulevard in the square, “it was easy to

jump to ‘Omigod, this is going to be catastrophic.’ "The nonprofits now want to consider everything from whether

the square’s parking lots could accommodate new,

high-density housing, to the correct theme and mix for the

center’s shops and businesses.

The idea of closing Shaker

Boulevard is off the table now unless the new planning

process reveals support for it, Menesse said. “We are not

going to talk about massive infrastructure changes,’’ she

said. |

Why the square matters

The travails of Shaker Square may sound

like a matter of strictly local interest, but like

Cleveland’s city-owned West Side Market, another historic

property that needs a public infusion and nonprofit

collaboration, the square is a major regional anchor.

The square’s future could determine,

for example, the fate of Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb’s $15

million initiative to revive majority-Black neighborhoods on

the city’s long redlined Southeast side — a major focus of

his still-young administration.

“Shaker Square is a gateway to Buckeye, Mount Pleasant,

Union-Miles, and Lee Harvard,’’ Bibb said recently in a

meeting with reporters and editors at

cleveland.com and The Plain Dealer.

The effort to rescue the square is part

of a larger flow of capital pouring into the city’s East

Side. The new investments include the Cuyahoga Metropolitan

Housing Authority’s plan to invest $250 million by 2028,

building more than 600 new housing units just west of the

square. The first two phases of the project, now underway,

are worth $79 million.

BBC is gearing up to revitalize the badly deteriorated

commercial corridor on Buckeye Road south of the square. The

city has spent $4.5 million on repaving and adding new

streetscapes along 1.4 miles of Buckeye, and

Cincinnati-based Fifth Third Bancorp. has promised to offer

$20 million in loans in the area, in collaboration with

Enterprise Community Partners, a national nonprofit.

It should also be said that the people

involved in the new Shaker Square initiative matter.

Menesse, the former director of economic development for

Shaker Heights, was part of the team that conceived the Van

Aken District, which has transformed the suburb’s eastern

flank. Johnson, at BBC, is deeply involved in the

aforementioned plan for Buckeye, which is dependent on the

success of Shaker Square, and vice versa. |

Big

ideas

Amid the new context, there’s no lack

of ideas for the square

Brandon Chrostowski, owner of the

EDWINS Leadership & Restaurant Institute, which trains

formerly incarcerated adults for culinary careers, thinks

the square should be turned into a large-scale, nonprofit

project devoted to social enterprise.

“Its mission would be to educate people

through trades, and businesses,’’ like his restaurant at the

square and adjacent operations along Buckeye Road, he said.

The square’s social and racial diversity makes it a perfect

place for such a venture.

Others see the square as the ideal

location for a new arts and culture district, or a vibrant

culinary destination.

“Shaker Square is and can be a place

for everybody,’’ said Matt Schmidt, director of

modernization and development for CMHA. “It brings so many

different backgrounds together.’’

In addition to seeking a new theme for

the square, Menesse and Johnson said that the new plan will

consider structural and physical problems baked into its

eccentric original design.

For example, the square’s leasable square footage of 168,000

square feet doesn’t provide enough income to care properly

for the property’s expansive public areas.

For that reason, the 2019 plan

suggested that the public spaces should be spun off

permanently to a nonprofit owner. That idea still looks like

a keeper, Menesse and Johnson said.

As for adding more housing, success may

depend on developer Joe Shafran, who owns a major property

behind the square’s southeast quadrant, with frontage along

Van Aken Boulevard.

Shafran bought the property, which

includes a double-deck parking garage, surface parking, and

a vacant retail strip, in 2018 for $800,000. He announced

plans to build a new apartment tower but didn’t follow

through. Now he’s offering to sell the property for an

unspecified price.

Menesse said it will be hard to come up

with a transformative vision without the Shafran property,

but she declined to comment on whether CNP would consider

buying it.

Shaker Square’s issues may seem vexing, but Clevelanders

have solved big urban development problems in Detroit

Shoreway’s Gordon Square, the Warehouse District, and the

Playhouse Square theater district. There’s no reason why

Shaker Square can’t be added to that list.

For Cleveland chef Doug Katz, who closed down his Fire

restaurant during the pandemic, the square needs more than

money and solid planning. It needs love.

“It was hard to watch it deteriorate

over time, and then you had the pandemic and the hardship in

the restaurant world,’’ he said. “I think it has so much

potential and love from the community. You have to put that

love back into it.” |

|

top of page |

|